Across the City of Angels, light beams are coruscating to a conga beat. Thrashing intersections, overlapping rhythmically until that final thrum makes for a collective pause, simultaneously falling still but only for a moment before the dance starts all over again in a quicker than breath motion: Go, go, go, STOP- Go, go, go, go, go, STOP (& repeat).

It’s 1941. We conga our way to the exterior of elite nightclub Ciro’s, known for its exclusivity devoted to Hollywood’s Golden Age starlets. But don’t fret! Tonight the everyman’s allowed to be privy, free of charge. The exterior’s unassuming columns and blinking neon signs are easily slipped past, heading inside. A lavishly decorated, Baroque inspired venue with tables arranged in the classic dinner-theater style layout, centered around a small stage, elevated just enough to keep the surrounding possibility of designated dance floor area separate. A glance around the room is all it takes to realize Tinseltown is everywhere, just as expected. 20th century movie stars, cultural icons of Americana film, immortalized by legacy. Know them? How many? Let’s find out.

Without hesitation shenanigans ensue: overenthusiastic Cary Grant, laconic cigarette girl Greta Garbo (whose shoe is set aflame by the impish and beloved Harpo Marx), horny Clark Gable unknowingly in pursuit of the final punchline, and so on. All these antics still in rhythm with that conga beat of course. More famous familiar faces, gestures, and voices pass through, each briefly caught in a joke of spectacle one after the next.All these antics still in rhythm with that conga beat of course. More famous familiar faces, gestures, and voices pass through, each briefly caught in a joke of spectacle one after the next, until it’s time for the main attraction, Bing Crosby announces: a stage performance of the sensual bubble dance, popularized by famous Burlesque performer Sally Rand. Steamy by war-time standards, tonight’s specific performance quickly earns loud wolf-whistles and a very male chorus of BAYY-BEE in hungry praise. Unfazed she continues, the very opaque large bubble moving in tandem with the (presumably naked) body, gracefully intentional in her hold.

At a table alone sits Peter Lorre— arm propped up by the elbow, palm cradling his chin as he watches, trademark buggy eyes cast in a droopy gaze. Quiet at first, then a breathy confession comes from his distinctly accented voice: “I haven’t seen such a beautiful bubble since I was a child.”

Welcome to Hollywood Steps Out.

I didn’t get the reference. Not in this Looney Tunes or Hair Raising Hare (1946), the other Warner Brothers made Peter Lorre cartoon I grew up with. Both featured such different versions of his caricature that I don’t even know when connected the two as one person. Unlike his soft-spoken bubble watcher who makes a celebrity cameo, “Dr. Lorre” is an evil scientist luring Bugs Bunny to his castle for the fuzzy orange mass of monster (Gossamer’s debut appearance!) who needs dinner. Creepy and wolfish with a sinister whisper to match, I remember finding him so human that it scared me. A childhood fear so vivd I can still almost feel it from sheer recollection to this day. It left that much of an impression.

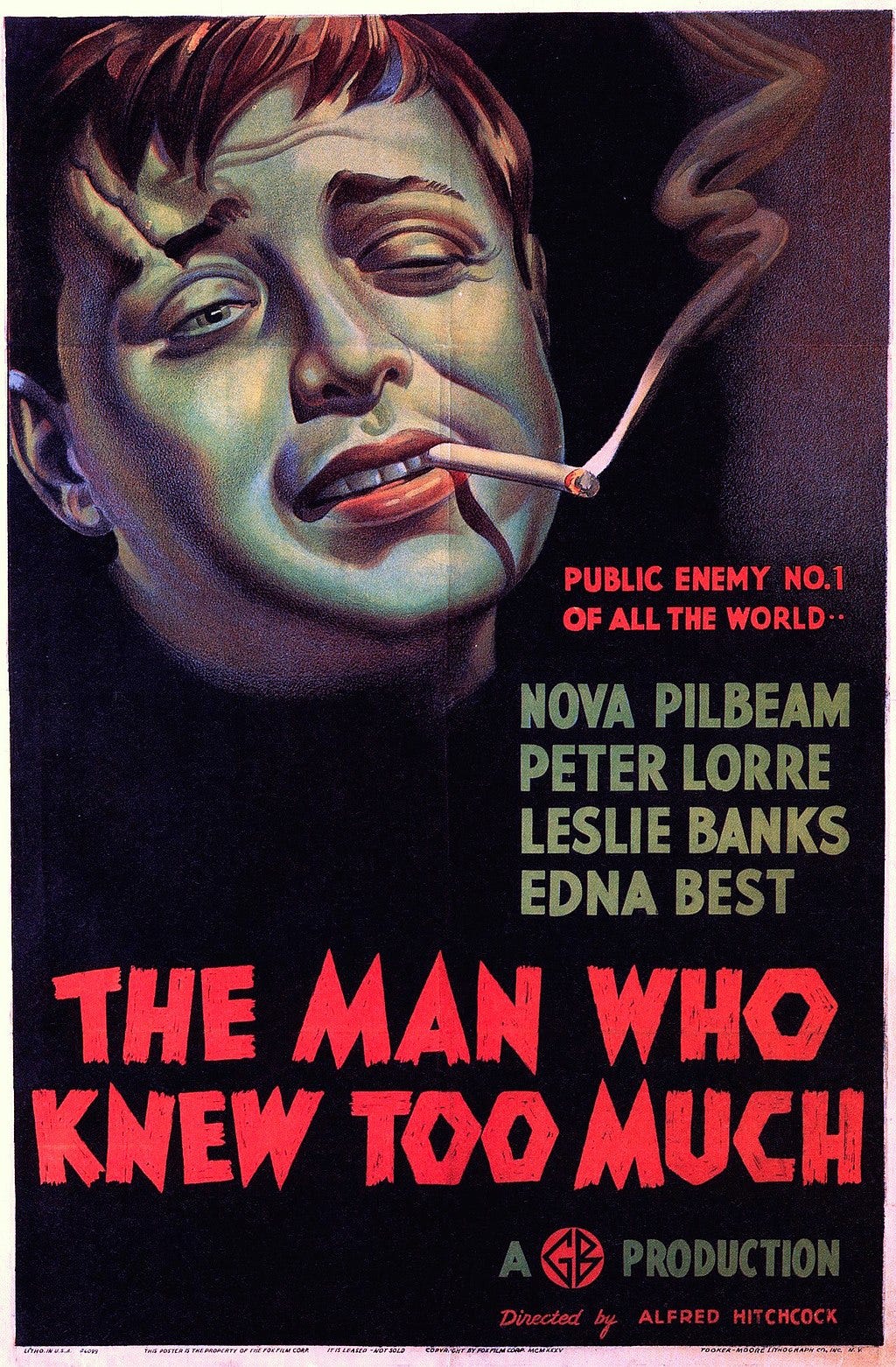

This pair of parodies wasn’t the only time I was fascinated by an image of Peter Lorre but still too young to actually recognize his face. Some time before 2008, when my parents hadn’t split up yet so we all were living in my original childhood home together, my dad downloaded a bunch of movies and set up his first Apple TV device. Scrolling through his sea of theatricaL posters attached to forbidden films that weren’t my kid-friendly options always felt so scandalous to me, chosen external images something I shouldn’t be seeing for films I’m not allowed to watch. Passing by and catching glimpses of everything I assumed to be the horror stuff my dad liked but could never show me, there was only one I’d pause at each time just to stare: A verdigris shaded portrait of a man’s head, floating amidst the blackness. His face is marked with a distinguishing scar down his forehead, its deep indentation seeping down past the eyebrow. One eye shut, he peeks lazily through the other, gaze fixed on something in the distance. Smoke curls upward from his orange lips, a gesture of fading translucence from the cigarette dangling in the corner of his mouth. Below him was The Man Who Knew Too Much, written in red.

I was mesmerized. His facial expression meant something and I wanted to know what, and if it was because he was the man who knew too much, and if he was then why, what made him that way, does he need to fix it by the end, how can he fix it by the end— something about him beguiled me, something I could not place. The feeling of wonder I observed this image of Peter Lorre with is just as vivid a memory as my fear, though they aren’t one in the same.

Once I learned who he was, the “Lorre Lookalike” simulacra was so obvious and everywhere, strewn across my childhood media consumption. He was the eye-popping sidekick maggot from Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride, nefarious King of Flan in Courage the Cowardly Dog, and even batty Bartok in my beloved Anastasia, just to name a few. These cartoon derivatives immortalize his surface level Hollywood persona, forming legacy at a remove. Still, they exist and were a crucial part of my childhood too.

Maybe conceptualizing this ongoing Peter Lorre phenomena after watching stuff like Cartoon Network for years set my expectations too high. I mean, surely someone with this much impact on American animation for almost a century has the throughly impressive living film career to match? Except when I actually started watching multiple Peter Lorre films I felt…disappointed?

It was almost a betrayal— he was supposed to have this illustrious, nuanced repertoire as the leading man like I always thought he would. His name and praised performances are attached to classic, iconic movies such as Casablanca and The Maltese Falcon— that coupled with the constant cartoon appearances (stretching well into the 21st century no less) formed the misconceptions I had about Peter Lorre the actor and his time on the silver screen. I never considered that watching these things might refute a narrative in my head already built on nothing, and yet…

Despite the possible implications, I’m not saying he sucks bad and so does every film he ever made— I want to make that really, really clear. Peter Lorre was a talented actor burdened by a horror typecast and secondary roles; these posthumous, made in his image cartoon sidekicks and villainous caricatures are a reflection of this too. There just are so many (the trope of it has been around for almost a century now) that I interpreted it as a Peter Lorre tribute rather than more of the same reductiveness he fought against his entire career.

He was born László Löwenstein in 1904 on the 26th of June. Despite his birthplace being Rózsahegy, Hungary (now Ružomberok, Slovakia), his parents were both German speaking Jews and he too would follow suit, growing up primarily in Vienna where his family had moved by 1913. There his acting career began, soon accompanied by the stage name Peter Lorre. M, directed by German Expressionism filmmaker Fritz Lang, was a breakout role that made Peter Lorre internationally known. Starring as Hans Beckert, he’s the insatiable child murderer being hunted down by determined police and mafia alike. This is actually my favorite performance from what I’ve seen of Peter Lorre’s filmography— when he first appears in shadow, whistling his leitmotif of “In the Hall of the Mountain King”, it’s stomach turning.

Multiple times I felt so deeply unsettled by the sight of him I literally had to pause it, exhale, say “Okay, this kinda is so creepy” aloud, and then I could resume my screening. Multiple times this happened! I haven’t been scared of a movie in so long, let alone a black and white one where you never actually see the murdering or any grisly related aftermath take place. But during M I deployed my newfound pausing ritual multiple times. He really was just that good.

M was so stellar it held influence over his remaining professional success, cementing the fascination with a pop-eyed leering shadow of sinister— not Peter Lorre. I believe it’s one of two career highlights that contribute to the villainous blueprint presentation for most Lorre Lookalikes, the other being MGM’S Mad Love (1935). He is Doctor Gogol in this sci-fi body horror Hollywood debut, a depraved surgeon who is pushed over the edge of insanity by his unrequited romantic obsession with one woman.

Just as bug-eyed and evil as he appears in M, Gogol’s another Lorre character as unpleasant as he is captivating to watch slowly unravel. His unshakably eerie aura is similarly goosebump inducing, especially during this one particular scene where he’s disjointedly playing the organ while his face fluctuates with the ever-increasing descent into madness. A bald, disquieting persistent little lunatic that is the film’s primary focus, Mad Love is good and once again Peter Lorre is good in it. Thus, the cartoon freaks continue to be made in his image.

His parts are much smaller when he isn’t the central psychopathic villain in this genre, but the performances are often just as great. John Huston’s first film The Maltese Falcon (1941) wouldn’t be the same without permed Peter Lorre as Joel Cairo, a supporting character with the most magnetism out of anyone on screen. The same is true for Frank Capra'‘s screwball comedy Arsenic & Old Lace (1944) in which he briefly reprises being a crazy surgeon, only this time it elevates the morbid movie’s silly mood.

Of all the early ‘40s classics featuring Lorre during his under contract with Warner Brothers studio era, it is Casablanca (1942) that surprised and confused me most. Sure I wished the actor’s presence was less secondary in these Old Hollywood hits and more like what I’d originally thought, but Casablanca felt more complicated than that. Because it’s so infamously iconic for being the greatest film made in the 20th century (it is), so are its stars—Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and presumably because he’s the main catalyst advancing the plot, Peter Lorre. His slimy Signore Ugarte is instrumental for what transpires, that’s true, but he’s only on screen for roughly twenty minutes. Perplexed while watching the movie last Christmas with my dad, I ended up literally asking him when Peter Lorre comes back— he doesn’t. I misconstrued Ugarte’s individual importance from Casablanca’s legacy as a whole, disoriented by all the Peter Lorre name dropping so attached.

I think these smaller yet still well acted appearances are the reason his animation derivatives are often sidekicks. It’s almost like an equation if you ask me: Peter Lorre horror + Warner Brothers career peak in secondary roles = perfect amalgamation for a cartoon character.

By the 1950s, things were different for Peter Lorre. As Julius O’Hara in John Huston’s 1953 adventure comedy Beat The Devil, Joel Cairo’s innate magnetism is nowhere to be seen. Weary and worn in even smaller roles, Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea from the following year barely offers him something to play. He was past his prime with increasing health issues. In the early ‘60s, Peter Lorre co-starred alongside fellow horror icons Vincent Price and Boris Karloff in a series of Edgar Allen Poe renditions— one last return to the genre. He died in 1964, aged 59.

He was too young to see his career into the late 20th century. Perhaps if he did, there would be more of a tether between him and his likeness— can’t you envision a REAL Peter Lorre appearance in Tim Burton movies a la Vincent Price in Edward Scissorhands, instead of him being the basis for maggots and other creepy side characters? Could there have been a boxed VHS set of his Warner Brothers highlights? Perhaps other, more successful ventures into writing and directing besides his sole German film The Lost One? If Peter Lorre existed in tandem with more cartoon versions of himself beyond Looney Tunes, I feel there would be more of a belonging to his own celebrity. Instead there’s this disconnect, one I didn’t even know existed because I fell into it too, despite learning Peter Lorre was a massive contribution to my beloved childhood cartoons. I guess this is my attempt at bridging a name and face back together, or at least a little closer now than they used to be.

**(Thank you again to my amazing high school teacher Peter Warren for answering my email with perfect films recs to watch for this piece, and to my roommate Theodora Eisenstein for her apt comment about Peter Lorre and Tim Burton)